LHCPlanning for the future

16 June 2014 | By

As someone who comes from a small mountain town, for many years I've linked the word 'summer' to 'seaside' and 'sun'. During my experience as a physicist working in ATLAS, I found myself associating the word 'conferences' to the word 'summer' more often than to the two above. Physicists work hard to meet review deadlines so that their result is made public before the start of the conference, often postponing seaside and sun. The reward is being able to present the work to an international audience: Summer conferences are the showcase of ATLAS results obtained throughout the year.

Even if in my case the results are still in the works, I was invited to chair the Physics Beyond the Standard Model sessions at the LHCP (Large Hadron Collider Physics) conference, at Columbia University in New York. LHCP is a new addition to the Summer conferences calendar and is already a well established appointment even though it is only in its second edition. LHCP combines two of the previous Summer conferences, HCP and PLHC, allowing physicists to economise on acronyms and travel.

During our week at LHCP, the sea was a few kilometres away so it didn't feature, but we had plenty of sun and plenty of results. Beyond the new ATLAS results on display (as detailed in Kate Shaw's post), the conference featured an interesting debate on the outlook of LHC physics for the coming years. The discussion between the six panelists (Natalie Roe, Steve Ritz, Hitoshi Murayama, Jerry Blazey, Sergio Bertolucci, Nima Arkani-Hamed) was moderated by NYT journalist Dennis Overbye, and was centred on the perspectives for physics at the LHC and beyond in the next decades.

The immediate, practical question that comes to mind is: why should we start thinking about the future so much in advance? We already have enough to do in ATLAS between completing 8 TeV searches and analyses and preparing for the upcoming 13 TeV run!

Past experience teaches us that planning for accelerators and experiments that require global collaborative efforts need to start much more in advance with respect to the start of operations. The first steps for the Large Hadron Collider happened more than 20 years before the start of the LHC data taking. Even though the concrete plan will certainly be driven by the results obtained at the 13 TeV LHC, now it's the time to start thinking about a global strategy that calls into action many countries in the world. Something that we scientists often take for granted is how well science works in terms of collaboration between different countries that normally aren't that fond of each other. Everything seems so effortless when discussing physics problems! Policymakers aren't as bright-eyed though, and if we want worldwide collaboration we need a robust framework in terms of international relations.

There are still many open questions in terms of targeted physics planning. As Fabiola Gianotti said, one of the most important questions is 'at which energy scale will we find the answers to the shortcomings of the Standard Model'?

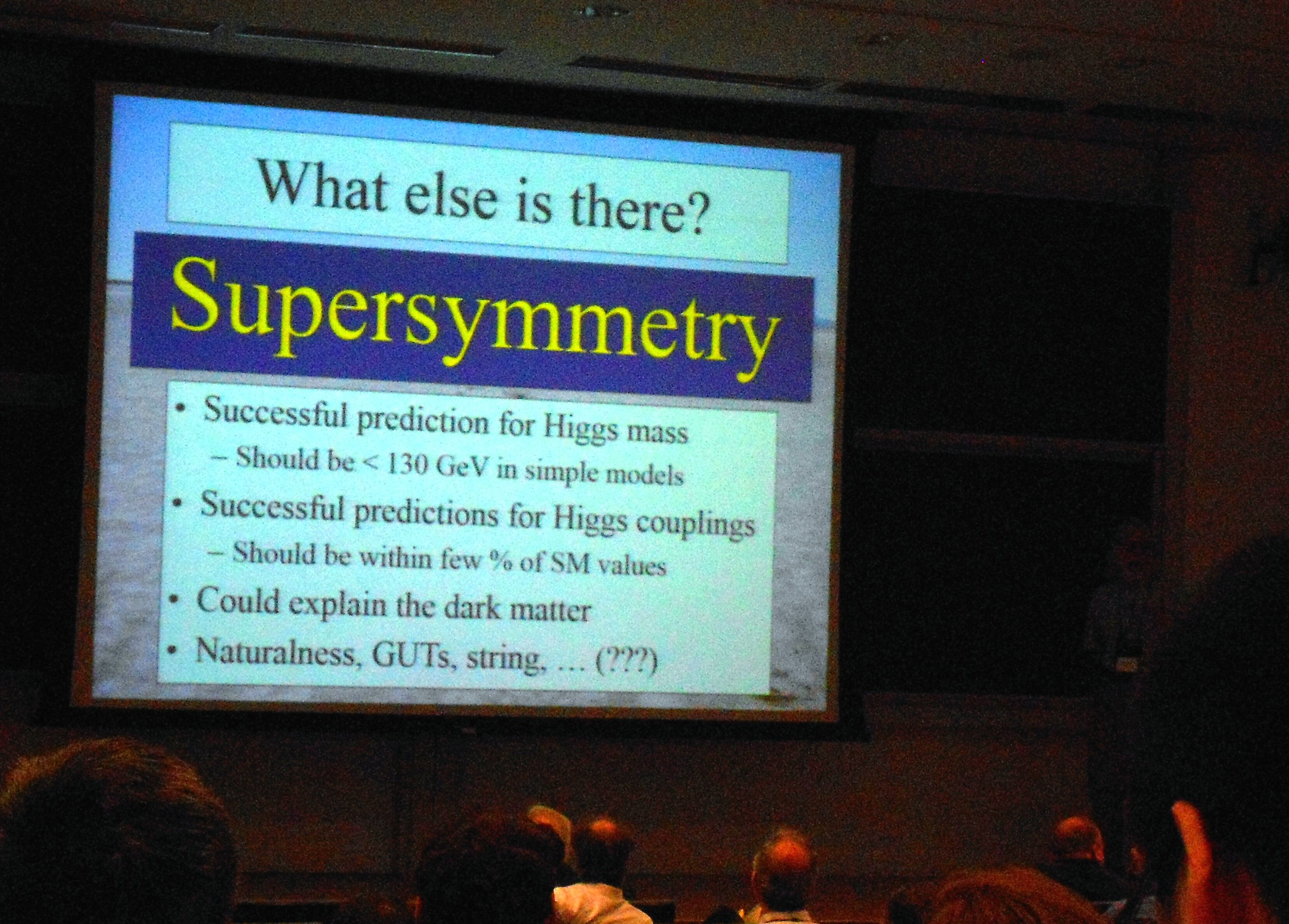

Many of us still strongly suspect that the energy scale of the LHC gives us a very good starting point to look for answers (see post by Zach Marshall about the SuperSymmetric particles that could be found at the LHC).

However, many of us also know that nature hasn't been yet so kind as to show us the signatures of the new phenomena that easily, and might not do so even in the upcoming LHC run. In the BSM sessions that I chaired, there was no claim of new physics discovery yet. So we know that we should plan for our current and upcoming searches to welcome unexpected and rare processes as they might help fill the gaps in our understanding of nature.

Fabiola's talk also highlighted that our recent successes might lead the way to new physics. The first LHC run pointed us to a new particle that is different to any other particle we know: the Higgs boson. The Higgs boson could be the particle connecting the known Standard Model world to discoveries beyond our current understanding. We must study the properties of the Higgs boson in detail; The choice of whether to do so at a linear accelerator or a large circular one will heat the debates of the next few years.

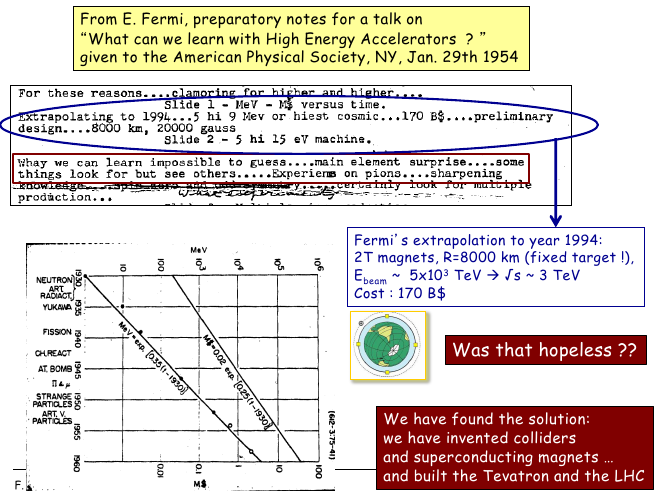

Another message from the discussion was that even though resources are limited we don't want to limit our ambitions. Enrico Fermi was quoted as an example: he mentioned TeV-scale colliders at a time when the techology was still science fiction.

If our vision of particle physics is one of a world-wide coherent research field, collaboration will help think of new technologies needed to make future particle physics research facilities happen. Our efforts should also be targeted towards making those technologies as affordable as possible, since we can't forget budgets are and always will be limited (let's not forget that the LHC expenditure needs to be put into perspective). But, as Nima Arkani-Hamed also pointed out, we should keep in mind that science is an investment and the pay-off (for everyone, not just for us scientists) is years from now. The questions we're pursuing now shape our culture and our world, now and in the years to come, so let's keep planning in order to answer those questions.

Caterina Doglioni