The power of perception

16 November 2011 | By

If you ask a child to draw a physicist, they’ll usually draw you a disheveled man in a lab coat. But looking around the hundreds of physicists eating lunch at CERN today, I saw many women, only one or two that could be classified as disheveled, and zero lab coats. Yet this image persists.

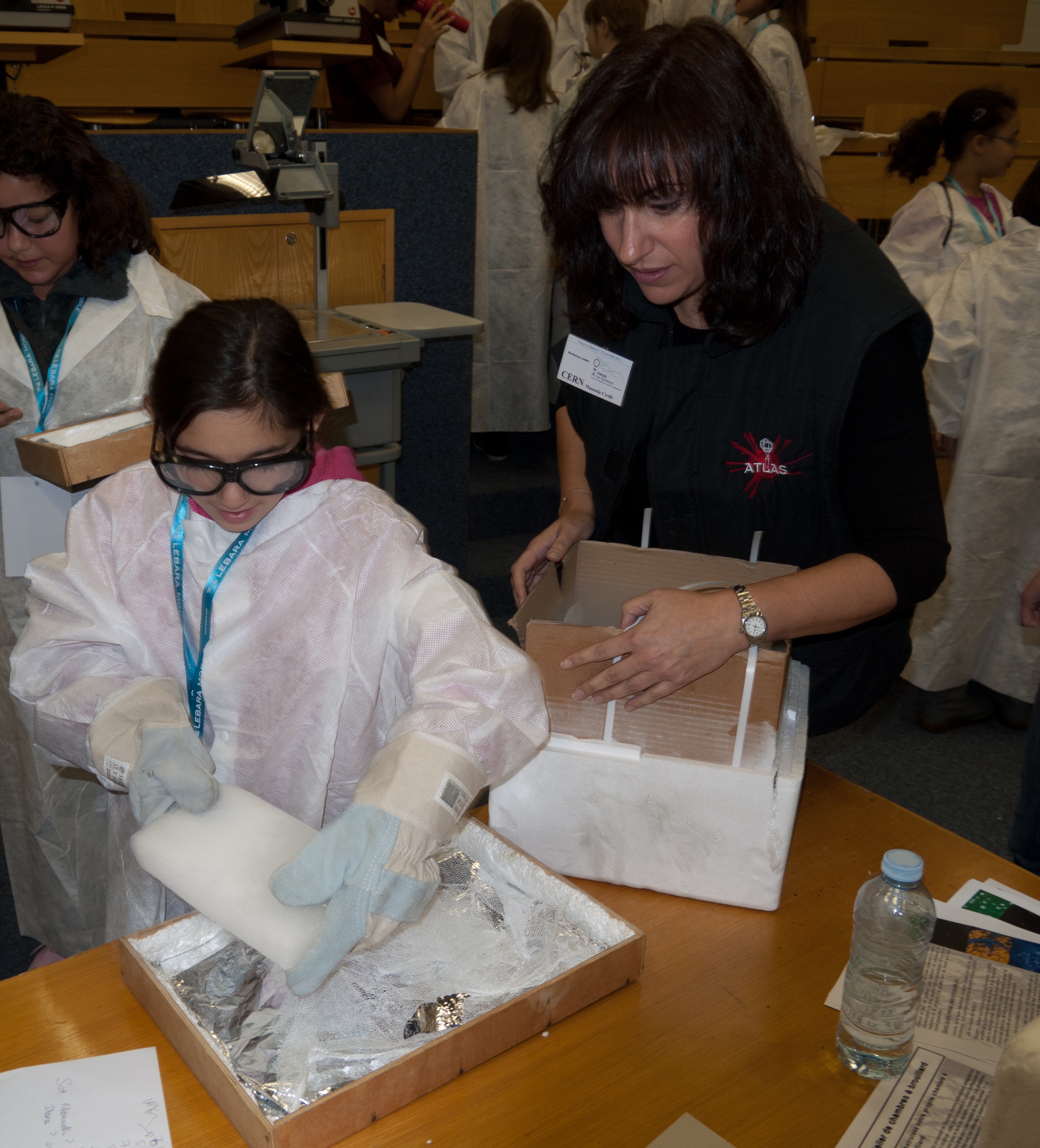

To bring a more modern and realistic image of physicists to school kids, myself and 12 other women from CERN participated in last weekend’s Expand Your Horizons conference. This all-day event is for girls between the ages of ten and fourteen to come and spend a day doing science experiments. From CERN we organized three different sessions: one involving experiments with liquid nitrogen; a second where the girls constructed their own cloud chamber; and a third where they did experiments which explained how the Higgs mechanism works, what is Dark Matter and other ‘Big’ questions. The message of this event is two-fold: science is fun and girls do science.

This is my favorite of all outreach events. I love explaining the physics at CERN to this age group. One of my classic opening dialogs is the following…

Me: How old are you?

Girl: Ten

Me: How old is the universe?

Girl: Uh… 100?

Me: It is 13.7 billion years old!

Girl: Wow!!! That’s crazy! [A short pause] So prove it!

Ten to fourteen is a great age to be teaching science. It’s an age where kids are young enough to be wowed, old enough to ask tough questions, but not too old that they stop asking those questions. It’s an age where they’re not afraid to challenge the fundamentals that we adults often assume are proven truth.

As a woman in science, I also feel the importance in sharing my life and experiences with girls of this age. As I was sitting in the cafeteria with the 260 girls participating in this event, I asked myself: Who were my role models when I was this age? For me, it was my mother who was a professor of nutrition and my grandmother who was a physician. But these two women aside, until my senior year at university I never had a female science teacher or professor. Would it have occurred to me to go into science if I hadn’t known a single woman who did science for a career?

Although the numbers of women in science and technology fields has been steadily rising since the 1970s, we still have yet to reach full equality in numbers. Today at the LHC experiments, 17 percent of all scientists, engineers and technicians are women. Nearly half of those women are students and post-docs, indicating that more women are entering the field. But a recent study from the World Bank and another from the Institute of Physics indicate that an additional factor should be considered: Between ages of ten and fifteen, many children have already formed perceptions about science careers and, for many girls, science careers are simply never considered. Based on these studies, it’s not that girls opt out of science, but rather that they never opt in, in the first place.

These questions of role models and opting in to science got me thinking, so as an experiment I asked 20 girls during the Expand Your Horizons event what they thought I did for a living (remember I am standing in front of a huge display of CERN and have just explained the physics of the LHC). Many of the older girls thought that I was a recruiter, while many of the younger girls thought that I was an assistant. Only a quarter of the girls thought I was a scientist or physicist. At first I was a little hurt (do I not look ‘sciency’ enough!?) But I quickly realized how a little can go such a long way to changing perceptions about scientists in general and women scientists in particular. At least 20 girls learned last Saturday that there are many female physicists, and over 250 girls learned about science careers in physics, medicine, the make-up industry, solar technology, food science and others. When it comes to role models and perceptions, just a single person can make the difference between opting out and opting in.