Are You Up for the Higgs Challenge?

16 June 2014 | By

It's been four weeks since the four-month long Higgs Machine Learning Challenge was announced. Almost 700 teams have signed up and more than 200 have beaten the in-house benchmark already.

Last year, ATLAS published a result observing a signal of the Higgs boson decay into two tau particles, this decay being a small signal buried in background noise. The Challenge's task is to develop an algorithm to improve the analysis using simulated ATLAS data by classifying events into 'two tau decay of a Higgs boson' versus 'background'. No knowledge of particle physics is required but machine learning skills are necessary.

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence in which computers are trained to recognize patterns in data. The top three teams will get cash prizes sponsored by Paris-Saclay Centre for Data Science and Google. The best algorithms may be applied to real ATLAS data. Winners will be invited to CERN to discuss their results. A workshop proposal is being submitted to the Neural Information Processing Systems conference in December 2014. If accepted, the winners will also be invited to contribute to the workshop.

We met with two of the organizers David Rousseau, high energy physicist, and Balázs Kégl, machine learning expert. Excerpts:

Why create an open challenge?

David: Only a few ATLAS people are experts in machine learning. Instead of searching through specialised machine learning literature, we put data on the web so people who write such literature can directly apply their algorithms to our data. For the challenge, we released our simulated Higgs decay into tau data, which was used to train the analysis for the result announced in 2013. With a good algorithm, we hope to improve this result. The winning algorithm may be integrated in our Toolkit for Multi-Variate Analysis (TMVA) and could be our final algorithm for the Large Hadron Collider's next run, to be used not just for the Higgs to tau analysis but other physics also. In the end, it could also be that what we've been using so far is the best for us. One never knows. Besides the algorithm, we'd like to connect the high energy physics and machine learning communities as we could really benefit from each other.

Balazs: Physicists have problems that are interesting to the machine learning community. I teach in a bi-annual data science summer school for physicists. Over the years, I met many physicists, including David, and during discussions, the differences in our approach sank in. The data challenge idea came early and people in ATLAS backed it up. Getting simulated data from ATLAS is very exciting for the machine learning community because they can apply their own techniques to real data in an important scientific context.

What skills does a participant need?

David: Participants should know how to write software. We have a kit to get started but for a good score, knowledge of classification algorithms is needed. We use such algorithms in ATLAS to separate the Higgs signal from backgrounds. Of course we will in particular study the best results submitted, to see if we can really use them in ATLAS to increase our chance to make future discoveries.

Balazs: ATLAS uses a two-step method, a classic machine learning technique followed by fine-tuning where the statistical significance, that is how clearly can I see the signal among the background, is maximised. This figure of merit is unique to physics analyses and not used elsewhere in machine learning. A competitor could improve on it by incorporating statistical significance right from the beginning into the algorithm, for which analytical knowledge in machine learning is helpful. If somebody does come up with a new method, it could be published.

Do physicists have an advantage?

David: Organizers of such challenges say that often machine learning people surprise experts with their approach and sophisticated algorithms, but physicists can invent clever variables using their expertise. They already know the features of the data which is made available for the challenge.

Balazs: The Challenge is a problem known to physicists. If they had a better solution, they would have found it. Machine learning people have a fresh perspective and tools that physicists may not. My bet is that a computer scientist will win this challenge.

FInd out more:

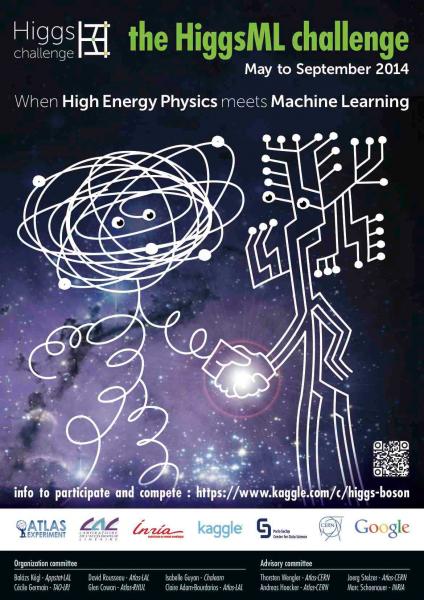

When High Energy Physics meets Machine Learning

CERN announces Higgs ML challenge