A view inside the ATLAS Higgs combination

28 July 2011 | By

Well it's been a few days since the Higgs presentations at EPS, and I'm just recovering from the lack of sleep. It's ironic that I have a newborn daughter, and my sleep deprivation is due to work. There is always a big push to get results ready for the summer and winter conferences, and it's a huge undertaking by the collaboration to finalize, review, and edit so many new results at the same time. I was primarily involved in the 'Higgs combination', and I thought I'd give a little bit of insight into what that's all about.

The first thing to know is that the Higgs boson is unstable, so if it is produced it will decay instantaneously into other particles. There are a few ways that it can be produced and several ways that it can decay. The various combinations of production and decay are called 'channels'. Like slices of a pie, the Higgs is divided into these different channels. The size of each slice is predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics and also depends on the mass of the Higgs boson. The goal of the combination is to bring together the slices and test the Standard Model.

Each slice of the pie requires a dedicated team of people to design the appropriate search. For instance, the biggest slice of the pie comes from the Higgs boson being produced via the 'gluon fusion' process and decaying into two W bosons. Those W bosons subsequently might decay into two leptons (l) and two neutrinos (ν). So the team studying the H → WW → lν lν channel will select a small sub-set of the vast amount of data collected by the ATLAS experiment that has signs of two leptons and missing energy due to the presence of neutrinos. That's the easy part. The hard part is to understand what one expects to see from 'background' processes. Estimating backgrounds is a bit of an art. The team uses a blend of theoretical knowledge, understanding of the detector, and the data itself to build a convincing story of how much background one expects to see. Often an individual search channel is like a mini-combination, subdividing the events into different types and bringing in control regions in the data to measure certain backgrounds. The search teams also have to quantify the uncertainty in this background estimate due to our incomplete knowledge of the detector and other systematic uncertainties.

To perform a combined search we must bring together the results from each of the search channels and form one giant statistical model of the data. The most tricky thing about this process is that a single source of systematic uncertainty in how the detector works will have an effect on multiple search channels. We call these correlated systematics, and to treat them correctly requires some coordination between the individual search channels. In the ATLAS combination, we had about 25 channels and about 65 individual systematic effects that we had to keep track of, and the situation is similar for CMS. For the last several years I've been working with a team of people to build tools to be able to handle this type of complexity. The main workhorse is something called the 'workspace' and it is central to the RooFit and RooStats statistical tools that we are using for the Higgs combination.

As you can imagine it's hard to coordinate something this complex with so many people involved, particularly when the individual teams are under pressure just to prepare their own results. We went through several iterations of the combination while the individual channels converged. Ahhh, 'converge', that was one of the most used words in the week leading up to the EPS conference. I think I was up until 4AM almost every night that week trying to get things to converge. Every morning I would wake up at 7AM to see what was going on at CERN, 6 hours ahead of New York, and then take my son to school.

Luckily we did converge on the main result the day before I left for Grenoble. I was on a train from Paris just hours before my talk when I learned that the labeling in all the plots had changed and that I would need to update my talk. I had to download all the plots to my phone with an international roaming charge…. it was going to cost me about $300 before I talked my mobile service provider into backdating an international data plan.

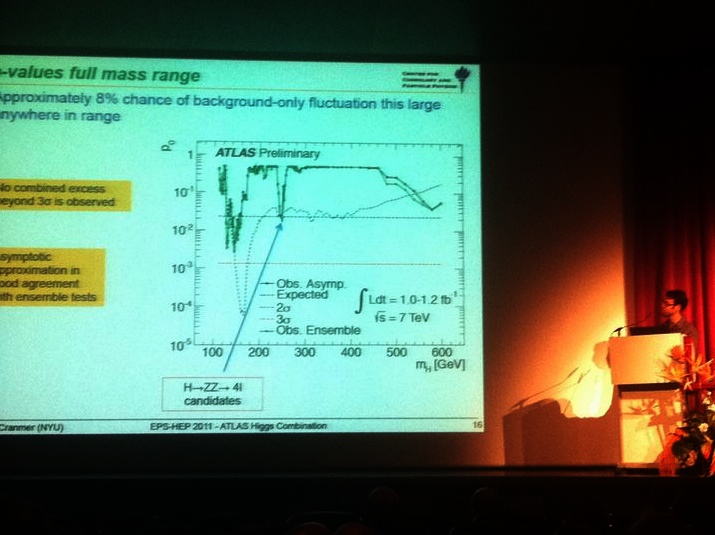

It was a real honor and a treat to present the results at EPS. The main results from the individual channels had already been shown, but the combination helps bring everything into perspective. When I talked I hadn't seen the CMS results, so it was a relief and a thrill to see that they were seeing a consistent picture. Both experiments excluded scenarios where the Higgs boson has a mass in the range 300-450 GeV, which is a big step beyond the Tevatron exclusions. Of course, the real excitement is the tantalizing hint of a Higgs boson. Both experiments see a broad excess of events, consistent with what one would expect from a Higgs with a mass of about around 140 GeV. That excess is dominated by the H → WW → lν lν channel, but both experiments also see a few events in the H→ ZZ → llll channel.

After the sessions completed, some members from ATLAS and CMS got together for a little champagne and to talk about the next step: an ATLAS+CMS Higgs combination to be shown in late August. It's definitely too early to say that we've discovered a new particle. And if we have found something, it's going to take a lot more work before we can say for sure that it is the Higgs boson. Nevertheless, these are exciting times and I'm sure that last week will be a highlight of my career.